How to Fix the Paradox of Primary Care – Healthcare Blog

Matthew Holt

If health policies think anything considers primary care a good thing. In theory, we should all have strong relationships with our primary care physicians. They should navigate around the sanitation system and arrive at Marcus Welby MD, etc., where needed. A fool like me thinks that if you introduce a relationship like this, patients will get preventive care, will get the right medication and take it, avoid the emergency room, and have a much less hospitalization rate and much less cost. This is the theory behind HMO and its descendants, value-based care and ACO.

Of course, there are many examples based on primary care systems, such as the UK NHS, or even Kaiser Permanente or the Arakan Article Slope Native Health Association in Alaska. But for most Americans, this is a place of fantasy. Instead, we have a system where primary care is the ugly stepchild. It is slowly going on and is disassembling. Even Walmart’s wealth doesn’t make it work.

There have been at least 3 types of primary care in recent decades. And, none of them really succeeded in developing the idea of “Lynchbin as a healthy population”.

First is a primary care physician purchased by and/or for large systems. The purpose of these practices is to ensure that the referral of expensive things goes into the right hospital system. These primary care physicians have long been losing money from employers – Bob Kocher said in the late 2000s that each doctor would be $1.5-250,000 per year. So, why are they accompanied by a larger system? Because they allow patients who go to the hospital to make a profit. Consider this NC system that ultimately sues the atrium of the large hospital system, because they only want recommendations. As you might expect, the “cost saving” benefits of primary care are difficult to find in these systems. (If you have time to watch videos of Eric Bricker on Atrium & Troyon/Mecklenberg)

The second is emergency care. Urgent care replaces primary care in most parts of the United States. The number of emergency care centers has doubled over the past decade or so. While the emergency room is under pressure, emergency care has replaced primary care because it is convenient and you can make an appointment easily. But this is not doing population health and care management. Typically, emergency care centers are owned by hospital systems that use them to generate referrals, or private equity pirates who try to increase costs beyond control.

Third, telemedicine, especially pharmacy-affiliated telemedicine, enables many people to use medication in a cheap and more convenient way. Of course, this isn’t really complete primary care, but Hims and many of her competitors can use utis, birth control pills and mental health medications, as well as common antibiotics for those candy and bald medicines.

This is not to say there is no attempt to establish new types of primary care

Oak Street, Chenmed and IORA (now part of a medical care) were established with the idea of providing primary care services to seniors for Medicare Advantage and taking financial risks to professional and hospital care in ideas similar to Kaiser and its competitors. As IORA founder Rushika Fernandopulle puts it, the theory is “double the expenditure on primary health care expenditure and reduce the overall cost by 30%.” It is not clear whether they get there.

Of course, like everything else in the U.S. Healthcare Street and IORA, earlier efforts such as Murkin, Friendly Hills, HealthPartners, etc. manage overall care expenses by taking primary care risks. None of these experiments were left alone by the Financial Brothers for a long enough time to see what would happen if they played. The stock markets in the 1990s and 2020s were filled with cemeteries of publicly traded primary health care groups, all with very promising starts. If they stay alone long enough to grow organically, we may see a different future. We may even see the future if health, transparency and others have managed to build their primary care/telehealth/navigation/product excellence centers. But it will take a while

Overall, although Sydney Garfield began prepayment from workers on the Great Cooley Dam in 1933, while this is the preferred policy solution, primary care taking risks remains a lonely business

Of course, this is the United States and you can still get excellent primary care, which will only cost you.

Silicon Valley multimillionaire to Jordan Shlain for $40KA in private medical and white glove service. On the other end of the scale, a medical person charges $80-200 a year from a year, gets a second-day appointment from a paid patient, actually responds to email NP and free telehealth services for emergency care. Somewhere in between is a group of doctors who choose the trouble of billing insurance companies and charge $500 to $5,000 a year. Then, using telehealth, home access, and NPs, provides a large number of primary care-based services, often in conjunction with on-site clinics in the workplace.

This means that the number of people who provide real Marcus Welby MD primary care in the community continues to decline.

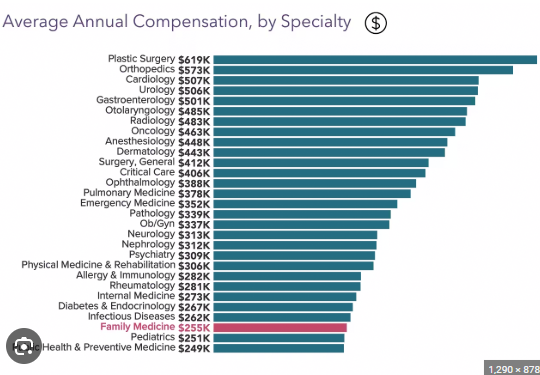

And it’s not difficult to figure out the reason. There are much fewer average primary school doctors than professionals.

Primary care costs are very low. The RUC (Relative Value Scale Update Committee) intentionally set it up as expert-led and basically sets Medicare fees, which most private insurers then follow. Therefore, most doctors tend to look at the top of this chart rather than the bottom of the slot they choose to live in. Health care in the United States is expensive because we have too many experts working on useful and useful care, and too many hospitals (as well as pharmaceutical companies and equipment companies) make money on banks. This has something to do with the chart.

KFF says nearly 50% of U.S. doctors have a pretty weird count in primary care, but that’s what many doctors are “primary care” and they don’t provide traditional primary care. This is of course wrong, but gives a hint for the solution.

There are 340 million Americans. We can give everyone a PCP and put it in a 600-person panel (as opposed to 2-3,000 typical PCP panels. That number happens to be provided by MDVIP and other concierge services. This requires 57,000 PCPs. This is about 60% of doctors in the United States.

So if we convert all currently licensed PCPs and add NPs, we can provide concierge services to everyone in the United States. These doctors will provide immediately and help patients navigate the system.

Its proponents believe that concierge medicine is not only better, but is often much cheaper than conventional care. MDVIP claims save Even after paying to the doctor, each patient is $2500, which is about 20% of health expenditure. My argument is that we can give each PCP $2K $2K (or every 600 patient panel), they can use it (I guess) $3-500,000 for practice, they can keep $700,000 for payment.

So my advice is that we provide everyone with really high-end primary care, very good payment for primary care documentation and save a lot of money. Obviously, we have almost enough primary care documentation to do this. To be sure, if they pay $700,000 a year, we’ll find more soon.

Matthew Holt is a publisher of THCB